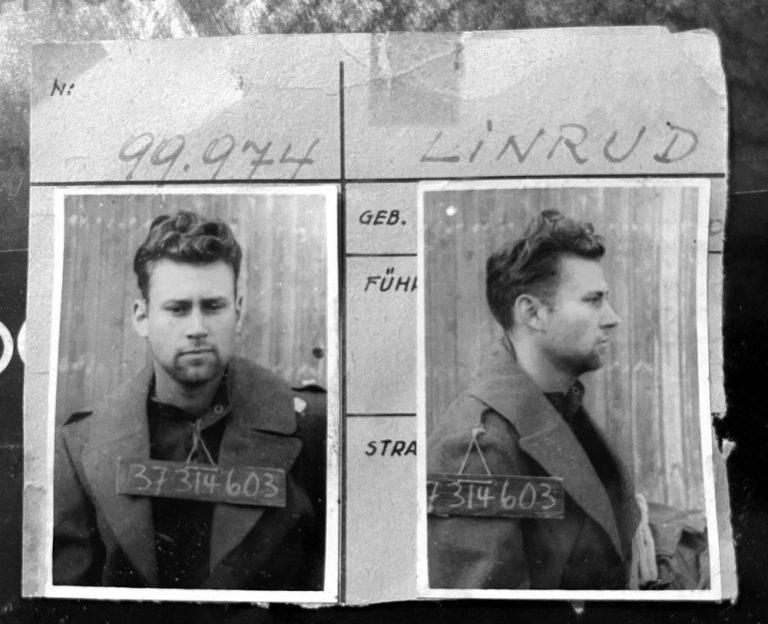

Art Linrud, Velva ND, was one of the World War II veterans who remembered Black Thursday, October 14, 1943, the day of the bombing mission to Schweinfurt, Germany. He was engineer and top turret gunner on B-17 Flying Fortress No. 42-3436. It was one of the relatively few planes without a nickname painted on its nose in the “Can Do” 305th Bomb Group in the 1st Air Division of the 8th Army Air Force in England. Linrud was forced to bail out of his burning plane. He became a prisoner of war. His account of Mission 115 follows.

Our plane took off in the early morning, amidst rain showers and dark, heavy clouds. We climbed to near 6000 feet before the clouds thinned out and the sun shone. The heavy cloud cover meant considerable time was lost getting into formation.

This was a maximum effort raid and one of the largest number of planes to go on a daylight raid deep into Germany.

Our fighter escort picked us up over the English Channel as we neared the continent, staying high above us and moving from side to side, protecting our top and sides from enemy fighter and rocket planes as we moved into enemy air space over the continent.

However, due to the time the bombers wasted getting into formation, the escorts’ fuel soon became exhausted, and they returned to England.

Almost immediately after our fighter escort left, enemy planes were seen climbing for altitude and readying for the attack.

From my position in the upper gun turret, it was difficult to get an accurate count. It was a matter of picking out one, lining it up in the gun sight, squeezing off bursts from two 50-caliber machineguns until the enemy plane swept past, then swinging the turret to pick up another attacking wave, picking out a plane, firing and following it though.

Unless a plane blew up in the gun sight view or smoked badly, a gunner never really knew if the plane was damaged or shot down. There wasn’t time to watch.

An enemy plane caught in the gunner’s sight was greeted with a hailstorm of bullets and streamers of red tracers as it came within range.

The action continued unabated as the attackers dove in at high speed, cannon and guns flashing along the wings. An occasional plane dove through our formation, barely missing the bombers.

On several previous missions, enemy pilots attacked cautiously and skillfully, using every tactic to the best of their ability and advantage. Today was different. It was a fierce air battle, a last encounter for many an airman on both sides.

As the formation moved deeper into enemy country, damage to several bombers became evident. Occasionally a plane, damaged and unable to keep up, would fall behind, then turn and head back, hoping to make it back to base or ditch in the English Channel, with crew members picked up by air-sea rescue.

Going home alone with a damaged plane usually meant further attacks from enemy fighters until either the fighters were shot down or driven off or the damaged bomber abandoned with crew members bailing out.

Smoke poured from an engine on a plane behind and to our right. It pulled away from the formation and was heading down in a dive, on fire and out of control.

Whenever I turned the turret to fire at an enemy plane I could see the action was everywhere, no part of the formation escaped the attack.

Suddenly, our plane shook violently from the impact and explosion of a cannon shell or rocket as it smashed into the rear part of our No. 2 engine, ripping a hole in the leading edge of the wing and leaving the engine a smoking mass of ruin. It was not more than 15 feet from my turret and from our pilot.

Fortunately, our pilot, Lt. Dennis McDarby, was uninjured, and quickly brought the plane under control. But, with the damage, we were unable to keep our place in formation and dropped down and started to fall back.

McDarby called on the intercom, checking on crew members-everyone was OK-and reporting that with the plane damaged as it was there was no way we make it to target with the bomb load. He said he was going to dump the bombs and go down in an attempt to fight our way back to a cloud cover at lower altitude. That way perhaps we could escape the fighters which continued to press the attack now that our plane was damaged and without the protection of the formation.

Smoke continued to pour out of the No. 2 engine area as we turned and dove down. Machinegun bullets hitting the fuselage sounded like hailstones hitting a tin roof.

Where smoked had been pouring back, flames appeared and, fanned by the wind, quickly spread to the fuel supply. Soon a huge ball of fire trailed back past the tail section of the plane.

Co-pilot 2nd Lt. Donald Breeden motioned me up front where pillow McDarby said, “Go down and remove the escape hatch cover. We’ll never get this fire out now.”

I picked up my parachute pack, snapped it in place, climbed down, grabbed the emergency hatch release and gave the door a kick with my foot. It disappeared as if by magic. A hole cut out into the sky appeared.

I was climbing back up into the cabin when I felt a hand on my head. I looked up to hear pilot McDarby say, “Bail out. I’ve already given the order. The wing is going to break off soon. We’re coming too.”

Backing down again, I hung my feet out the door and sat on the edge. Glancing into the nose section, I saw navigator 2nd Lt. William Martin and bombardier 2nd Lt. Harvey Manley getting ready to follow me out. With a quick departing wave, I gripped the “D” ring and tumbled into space.

Onrushing cold air alerted me to give a firm pull on the “D” ring. There was a sudden slap in the face from the chest parachute pack as it passed upward and then a jolt as the chute filled with air.

Being suspended in the quietness of the air was a contrast to the clatter and vibration of machineguns, tension of battle and steady roar of engines. How quickly it had changed!

The roar of a German plane passing overhead, too close for comfort, quickly brought me back to reality. Several chutes were visible in the sky.

My eyes caught sight of our plane, below and to one side, falling out of control. The burning wing had broken off.

As the ground moved up to meet me, what before were small dots were now civilians and German soldiers moving about to intercept landing airmen. I came down in a small field, landing on my feet but falling to the ground from the impact.

Not more than a few minutes later, after freeing myself of the parachute and getting to my feet, I heard a statement that was to be heard often for the next 18 months.

Spoken by a German soldier with a pistol pointed at me and interpreted by a civilian, it was: “For you the war is over. You are now a German prisoner of war.”

I had landed at the edge of a small town on the border of southern Holland and Germany, landing among soldiers stationed there. The officer in charge quickly had me searched for sidearms. It was hard for him to believe I had none.

We made our way to a small group of people gathered in a circle about 100 yards off. I immediately recognized Sgt. Dominic Lepore, the tail gunner from our plane, sitting on the ground, his hands covering his head. A 20 mm shell had exploded above and behind him in the plane, sending many small pieces of metal through the flying cap and into the back and top of his head.

A bicycle was brought and we sat him on it. With the bike pushed by two civilians, we mad our way into the town and were taken to a building that appeared to be the town hall. In a few minutes, a civilian doctor came and attended to the wounds in Lepore’s head.

There was a lot of commotion-people and soldiers coming in and out, loud and excited talk in a language we didn’t understand.

Soon more Americans were brought into the hall. Among them were Sgt. Ben Roberts, the ball turret gunner, Sgt. Hosea Crawford, the radio operator, and McDarby. McDarby was limping badly from an injury to his ankle and foot.

View our full Tribute to Service: https://www.nordaknorth.com/newspapers/northernsentry/online-issues/tribute-to-veterans-2024/